Incunabula and the Keio University Library Collection

Pagination

027

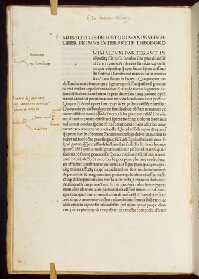

Aristoteles [Aristotle], De animalibus (Venice: Johannes de Colonia and Johannes Manthen, 1476)

De animalibus (Tr. Theodorus Gaza). Ed: Ludovicus Podocatharus

IIIF Manifest

IIIF Manifest

Scholars of natural history have long collected and categorized animals, plants and minerals, and thus systematized their understanding of the natural world. As a subset of natural history, herbalism deals with plants as helpful 'medicines'. In the 1980s a Japanese writer, Hiroshi Aramata, published 5 vols of the Atlas anima (Tokyo: Heibonshiya, 1987-91), in which he introduced the work of Gesner and Buffon, who produced many illustrations in the 17th and 18th centuries. Aramata's work eventually led to a rediscovery of Western natural history in Japan.

The study of natural history traces its origins back to Aristotle (in Greek) and Pliny (in Latin). Aristotle was a great observer of the natural world, and produced various scientific writings, such as Historia animalium, De caelo and the Meteorologica.

Of his varied interests, animals attracted him the most. His De animalibus consists of three volumes: the Historia animalium, De partibus animalium and De incessu animalium. The Historia animalium focuses on the shape, reproductive biology and pathology of several types of animals; De partibus animalium discusses the functions of animal organs; and De incessu animalium details the growth processes of animals. Aristotle wrote De animalibus based on the writings of Homer and of the historian Herodotus, as well as on his own observations, and the content of his book still had great appeal even up to the 15th century. In stark contrast to Aristotle's book, which probed into the internal workings of animals, the natural histories of the 17th and 18th centuries came to value more superficial observation and narrative.

According to ISTC there are four editions of De animalibus, which is a translation of the Greek text into Latin. The oldest of these is a 1476 edition, which is considered to be the standard edition. The Keio copy was edited by Cardinal Ludovicus Podocatharus in 1476, and translated by the Greek scholar Theodorus Gaza.

The book was printed in Venice, where the printing market reached the height of its prosperity by two German printers, Johannes de Colonia and Johannes Manthen; the latter made Venice a trade centre for punch and matrix type, together with a French printer Nicolaus Jenson (see IKUL 029), who is said to have created roman-style type. Others printed the Gaza translation in Venice in 1492, 1495 and 1498.

The Keio book, which was bound with vellum in the 18th century, has 251 leaves (it lacks one leaf) and 35 lines per page, in the Venetian style. Certain features – such as the slight contrast between bold and thin lines, the fact that the middle line of the 'e' leans to the upper right, and the fact that the strokes of certain letters like 'M' have a serif known as a scale – mark it out as exemplary of the Venetian style, c. 1470.

(KI; trans. by KT)

詳細情報

- Author

- Aristoteles [Aristotle]

- Place of Publication

- Venice

- Printer

- Johannes de Colonia and Johannes Manthen

- Format

-

fº

- Date of Publication

- 1476

- Binding

-

16th-century vellum over card boards.

- Bibliographical Notes

-

252 leaves; running title and marginalia in a contemporary hand; spaces for initial capitals.

- ISTC

- ia00973000

- Reference

- Goff A973, IJL 027, IJL2 034, HC 1699*, BMC V232, GW 2350

- Shelfmark

- 120X@788@1

- Acquisition Year

- 1988

- Provenance

-

Myron Prinzmetal (bookplate).